The Distilled Objectivity of Digital Foundry

Digital Foundry is simply the best form of mainstream game coverage because it satisfies the gamer craving for objective measures of quality in an otherwise subjective experience. Digital Foundry’s attention to detail when it comes to the technical aspects of games as products is something I find fascinating compared to traditional game reviews. This is mainly because their methodology is so different compared to most game assessments that exist in the mainstream, they’re technical, thorough, and eerily better than many forms of game criticism.

If you grew up playing games and reading games media any time in the last 40 years, you too have probably encountered the obsession with game hardware so aptly wielded against children and teens to build consumer loyalty. This obsession with technology, in the absence of much specialist knowledge about it, sometimes leads to games feeling like they have a somewhat objective aura about them, a flavour of certainty. To be fancy, you might call this the technological promise rhetoric of games, that is to say games promise to use technology to make our utopian desires real, yet they are still software operated by a machine. Software that obeys the cold, procedural logic of machines. After all, a piece of software functions correctly to its purpose or it does so poorly, if at all. This is something consumer-facing review outlets have struggled with for a long time since games are obviously highly subjective experiences given the diverse range of preferences different genres, styles, themes and content could apply to. When considered holistically, each game speaks slightly differently to each player.

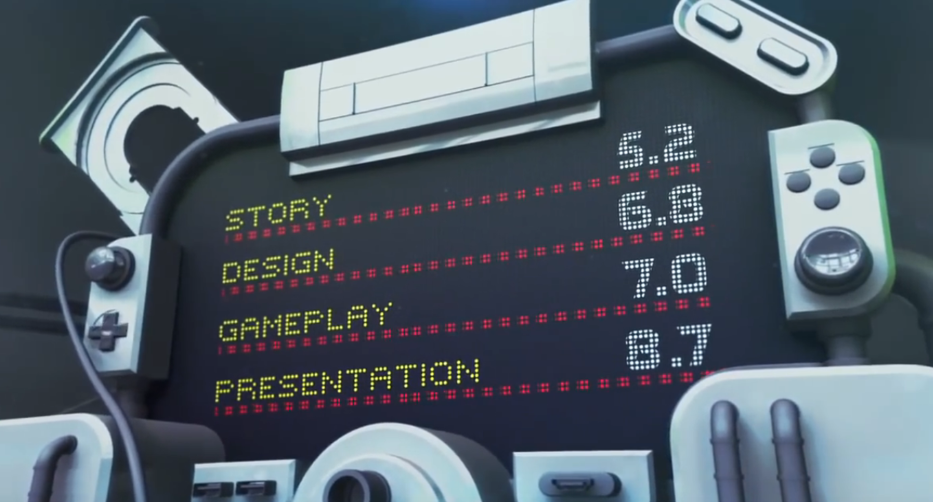

At the heart of every media review is a struggle to rank. A struggle to accord with/shape public opinion and ultimately determine where a game falls on the spectrum of best to worst. Hence, the multitude of methodological decisions facing history’s games reviewers. Do we use the five-point scale, the ten-point scale, the hundred!? The sextant of stars and points, our guide to the shores of bliss. Yet, the rating out of 10 has never really been much more than a gut shrug you might make to a friend to summarise your feelings quickly and intuitively. Entire waves of games critics will still struggle for relevance in the landscape and so mostly cater to consumers’ feature-driven concerns. Critics often struggle to properly convey deeper subjective aspects of games and or nuanced technological issues and so we are left with a particular voice of games criticism.

Gametrailers.com Reviews used the component rating method

Gametrailers.com Reviews used the component rating method

The vocabulary of game reviews is descriptive and breaks things down in ratings out of 10 even for individual components. Description is how one seeks to begin the scientific inquiry into what the game is. The consumer awaits answers to burning questions such as: ‘Is this a roguelike?’, ‘How many classes are there?’, or ‘Is the kinetic combat system only satisfying if you’re willing to narrow your playstyle to a relatively small window of options?’. Questions mostly removed from reflexive experiential questions of what games mean and instead targeted on the facts. Tell it to me straight. All manner of titles and adjectives are employed in the great description such that you’d think the audience of such criticism craves cliche. Is this game a ‘benchmark’, the ‘paradigm shift’, or the dreaded ‘one to avoid’. Did it ‘move the genre forward’ and is it ‘worth picking up’? As long as the game is good, we can be certain that ‘fans will rejoice’.

Here’s an extract from IGN’s review of Dishonored 2, specifically the concluding paragraph:

With two unique sets of skills to play with across 10 themed chapters that keep things interesting and a gorgeous, evocative world that feels alive, Dishonored 2 is a remarkable experience. Though I would have liked a little bit more originality in its central story, which again revolves around a usurper to the throne, it’s the stories that I’ve created on my own using its many creativity-enabling powers that I’ll remember, every graceful, fumbling, and hilarious one of them. I’m compelled to create many more in the months to come.

9.3/10

To be very clear, I’m not trying to shit on this writer because this kind of descriptive product writing is exactly what game review outlets need and their audiences are apparently fine with. It meets its function well and does the job of confirming a recommendation and according with a basic groupthink opinion about a big blockbuster release. It gives me the facts. As a fan, I know whether or not I should rejoice strenuously based on the tick boxes and distilled pros and cons.

The purview of most game critics, now often recovered from the remnants of former press outlets, is mainly to keep a finger on the pulse of the zeitgeist and help steer the general ‘what people are saying’ about a given game. In some cases you get the sense that this kind of conversation is determined far before the release of a game after having taken the blood pressure of public opinion on Twitter. This extends to the degree that bad reviews across the board for a game is treated as its own reflexive confirmation that judgement has been rendered properly in case you mistakenly thought that you as an individual might enjoy a slightly janky or imperfect title.

Digital Foundry, on the other hand, is an outlet that primarily reports on technical performance of games, often in the context of how smoothly they run on various hardware and what graphics technologies make them dazzling. It also occasionally dabbles in retrospectives that look at how different gaming hardware or version of a game (often a recently re-released, or remastered game) compare to today’s standards. It’s hard to really call it critical analysis in the traditional sense and could be said to be the most honest form of the traditional videogame review. It is consumer information presented in an informative and entertaining way and it’s the best at that mission statement, I argue, than literally anyone else writing reviews. At least in the mainstream of games criticism.

In a world where the logical endpoint of AAA crunch and hubris emerges in projects like Cyberpunk 2077, Fallout 76, or Redfall, and games cannot contain their bugginess from hungry hordes, Digital Foundry is the just and levelheaded arbiter. It fights technology with technology to determine the best platform, expose the mismanaged ambition of studios, and make the all-important purchase recommendation.

Digital Foundry absolutely without reserve is the best games review channel for one simple reason. The frame capture analysis tool don’t lie. This objective axiom is irrefutable. A high and stable framerate is better. A robust image quality is better. The texture pop-in happens at this or that distance. A game performs well or it doesn’t. The technological promise games suggest in their advertising can be most thoroughly assessed only by something like Digital Foundry. In some cases, a game may come to prominence for its outstanding technical competence, something most reviewers may totally miss due to the literacies required.

Occasionally Digital Foundry do actually comment on their opinions on the games they look at and always feel a little more naturally expressed since they acknowledge that game’s technical ambitions aren’t always aligned with their creative ones. They’re ‘non-expert’ critics when in the Digital Foundry mode so it ends up being a neat mix of tech expertise and amateur critique - closer to what a friend might casually state. Part of the reason this gets through I think is to do with the primary purpose of DF being to examine the technological promise. There’s nowhere near as much pressure on them to deliver the opinion that accords with the reader when trying to put an objective number score on something many people will like or dislike for a plethora of reasons.

Another way in which Digital Foundry is manifestly the best is that the diversity of reviewed content is higher with Digital Foundry and I’m not talking about demographics. Digital Foundry routinely looks back at systems, games, rendering techniques, and technological architecture in the same detail and treatment as their contemporary review fare. Not only that but their criticism arguably becomes more and more relevant and rich to explore over time as more and more platforms are developed and new technologies emerge. A frequent argument against awards shows and criticism is that it is very short-term, it aims to provide an evaluation of something as soon as it releases or within the same financial year. Often it’s useful to take the long view and see how a game might hold up in the long run and across a myriad of different ports and platforms to distill the essence of a game. Many YouTube critics do this although it is primarily through the lens of nostalgia. Digital Foundry once again have the compass of objectivity on their side to provide a focused exploration of whether a game really does ‘hold up’ and how impressive (or not) their technology was for the time.

Evocative of the strange dividing line between options and accessibility. People care greatly about frame rates, image quality, dynamic lighting, whether the aliasing is sufficiently anti and how. But as soon as the option extends to literally how I, as a person with capabilities different from another person, might prefer to play video games, it becomes a very awkward battle of leisure morality. This is a bit of a tangent regarding accessibility so all I’ll say is the technological promise of games is different but similar to the question of accommodating player preference with regards to skill. Gamers as a whole care about some options (that relate to technological promise in a sort of conspicuous consumption/good taste frame) but not others (that also relate to technological promise but put you in a position of vulnerability).

There’s what I’ll term a ‘double aesthetics’ of games that I think DF makes evident when it comes to visual analysis. Image quality is a frequent criterion that is assessed by DF which is primarily concerned with the image output but this is not the same as aesthetics, although they are related under the umbrella of representation, constituting a ‘double aesthetic’. Image quality is an objective quality, the video output is of a particular resolution, aspect ratio, it may feature compression artifacts which noticeably distort the mediated image. Interestingly, this is somewhat divorced from a game’s broader style and art direction. A game may appear drab but have perfect image quality, another might have lavish and provocative visual direction but a stuttering frame rate and frequent screen-tearing. Image quality can even change depending on context which Digital Foundry deftly explains in cases where temporal anti-aliasing ghosts might affect a game that otherwise looks fine in still screenshots, but not in motion.

Digital Foundry does occasionally speak to art direction in some cases where image quality overlaps, particularly in cases of older games where textures that worked on an older monitor may be quite ugly in high definition. The opposite can happen as well where a game may have assets and art, too detailed for the distance it actually renders through the camera. But their comments on art direction are still really predicated on technical grounds like the physical qualities of light, colour, and shadow. Not so much what they mean or evoke.

OpenCritic, and other review aggregate websites, are the culmination of the current game assessment landscape. There are even fantasy football style sites that will allow you to draft games for a year which will reward you based on their aggregate review scores. Playing the game reveals to you the artifice of much mainstream games criticism very quickly as it becomes clear that scores are dictated by the limited tastes, experiences, and PR function of reviewers as a class of people in the games industry. These leagues are actually pretty fun to play in, there’s even some that have people competing to draft the lowest reviewed games in a year. However, playing in these leagues makes it pretty clear that anticipating the review scores of games across a year has a lot more to do with being proficient in market research and zeitgeist awareness than it does with the question of whether a game will provide a rewarding time for a given player.

The YouTube channel Crowbcat puts out videos that often compare older and newer games for the features (mostly technological) that the former has and the latter lacks. The channel has a similar technological promise rhetoric at play although these videos tend to implicitly argue that attention to detail is lacking in modern games, usually sequels in long-running series like GTA or Resident Evil. This is where the objective facts about the technologies behind games then become a means of subjectively evaluating whether a given game (and its devs) is lazy, worthless, or soulless. Crowbcat’s comparisons do reveal interesting differences but sometimes come across as privileging a particular technological promise as if all players value it the same way.

Digital Foundry kinda obscures the conversation. Its editorial line is generally more fair and generous in terms of simply assessing the technology. No cruel assumptions are made about the people who made the thing, or why a given choice was taken. Digital Foundry also has a more redemptive approach when looking at older titles, equal parts celebration of ingenuity and ambition and technological assessment. A good example is their retrospective of true HD games released for the Playstation 3, or their episode on all the versions of Virtua Racer ever released.

The average person can’t figure this stuff out for themselves easily so having them provide this is very informative, but maybe not always in a way that a person not personally fascinated by graphics technologies might appreciate? Yet, it’s still engaging because of how it is conveyed through Digital Foundry’s signature point-to-point structure, data visualisation and ‘because X this results in Y’ format. Could broader critical analysis of games be explanatory in such detail in the same way?

Although it’s a truism, as long as videogames are software, technology will always be a component of their assessment. Digital Foundry is fine, good even. Like I say, I enjoy it because of how unique the analyses are compared to review-based criticism. But imagine a world where technological assessments are routinely supplemented by equal attention to detail regarding more subjective aspects of games, or, now this is crazy, how they exist outside the commercial frame. And I ain’t just talking about if reviews move beyond describing a game and attaching a number. Unfortunately as far as mainstream criticism goes, it’s all we’ve got. The competing literacies of game criticism mean that if we’ve described or technologically disassembled a game, what’s left? The broader audience certainly isn’t interested in hearing more and if they are, the most effective route for them i s to seek out direct discourse with other players in more niche corners of the internet like forums, YouTube comments, or Discord servers - although even this can be a dicey prospect. Digital Foundry are so thorough when it comes to assessing the technological promise, it’s hard not to be envious that similarly detailed criticism couldn’t be extended more regularly. Video essays can sometimes scratch this itch but it is sad that these either tend to be so exhaustive they feel empty or are so hidden and niche one wonders if more than 10,000 people on Earth really care about games for more than their technological promise. At least we have Digital Foundry.

- Captain Love